History

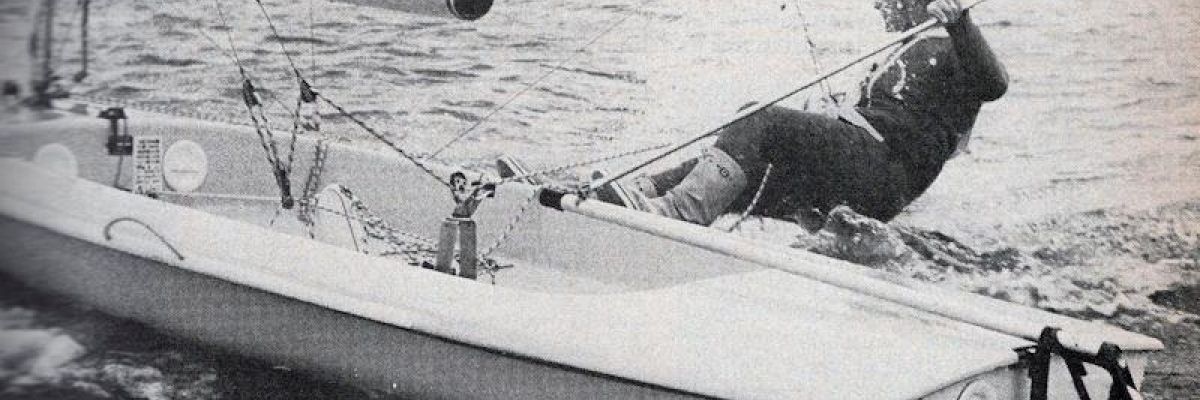

The Contender dinghy was originally designed back in 1967 by Australian Ben Lexcen as a potential Olympic successor to the Finn class. The boat won the 1969 Olympic trials, but for a variety of reasons was never adopted as an Olympic class

THE EARLY YEARS B.C?(BEFORE CONTENDERS)

There are so many classes today, that it is hard to imagine a time when the choice of dinghy for a single handed sail...

ON TRIAL

To choose their new class, the IYRU held a set of trials at Weymouth in the autumn of 1965. The International Canoe w...

DOROTHY IS DROPPED

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, an Australian Skiff designer and sailor had also picked up on the IYRU sea...

THE CLASS IS LAUNCHED

To help the Contender along, through the difficult early days, a Launch Committee was formed from the ‘movers and sha...

A STAR IS BORN

La Baule was hot, sunny and with light winds. This suited some of the competitors, but not those boats with a high we...

FIRST WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS

In 1970, the first World Championships were held at Hayling Island, an event won by ‘wild man’ Dick Jobbins. Dick was...

COMPETITIVE HIGH SPIRITS

The Europeans at Hayling were won by one of the sailors from the early days of the class, Joachim Harpprecht, who bea...

ANTIPODEAN HEAVEN

With the Contender now very much an established international class, many of the names and personalities who had been...

GLOBETROTTING

For 1981, yet another new venue beckoned, Toronto. This time the front of the fleet was dominated by a battle between...

THE MAGICAL 3 FIGURE MARK

By now the fleets at the top events were reaching that magical three figure mark, a milestone that was passed when 11...

CALIFORNIA DREAMING

This second phase of the Contender history ended with the Class back in the US, at Santa Cruz YC (home of Gil Woolley...

21 TODAY!

But still no key to the Olympic door for the Contender!

The third decade of the Contender started with the fleet bac...

ANOTHER YEAR, ANOTHER ISLAND

this time Sicily! The event looked like being another Brit benefit, until, on the last day, Andrea Bonezzi came fro...

NEW KID ON THE BLOCK, THE RS 600

Away from Stuart and his interest in Ovis Aries, the news was of the new kid on the block, the RS 600. Whatever the a...

BACK TO THE ROOTS

In 1997 the wonderful city of Sydney was alive with Olympic fever as the preparations for the Games went into overdri...

ISLAND HOPPING

The following year the fleet chose another exotic island location for their championships. Sardinia is famous for hos...

GONNA PARTY LIKE IT'S 1999

The end of the millennium, the ‘Millennium Bug’ and yet more politicking from ISAF. They already had two top Internat...

FAREWELL TO FREDDIE

Back in Europe, Graham Scott won the Hellerup Europeans and must have looked the firm favourite for when the Worlds c...

THE DOCTOR CALLS

There was no lack of wind at Fremantle, where the famed ‘Fremantle Doctor’ blew with its usual ferocity. The heavy we...

THE CONTENDER TODAY

The International Contender class now has fleets in more than twelve countries throughout the world. There are over 2...